Insights < BACK TO ALL INSIGHTS

New Jersey Sports Gaming In Flux: State Moves to Regulate Daily Fantasy Sports While Legalized Sports Betting Faces Greater Hurdles

New Jersey Sports Gaming In Flux: State Moves to Regulate Daily Fantasy Sports While Legalized Sports Betting Faces Greater Hurdles

By: George Calhoun

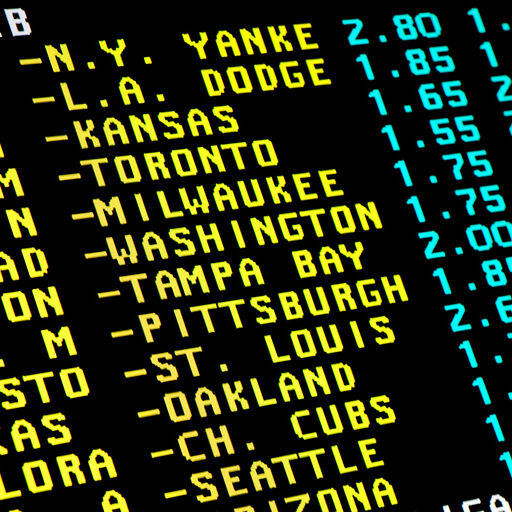

In a highly-anticipated brief by the Solicitor General, the United States argued today that the Supreme Court should not take up New Jersey’s challenge to federal laws preventing it from legalizing sports betting. Despite President Trump’s knowledge of, and seeming sympathy towards, the gaming industry, his Solicitor General claims that the “limited practical consequences of the question presented confirm that [the Supreme Court’s] review is unwarranted.” In the view of the Feds, an issue of importance only to New Jersey is of no significance, even if it would pave the way forward for similar action in other states. The brief throws cold water on New Jersey’s hope that the Supreme Court will hear its challenge to The Professional and Amateur Sports Protection Act of 1992 (“PASPA”), dashing hopes that President Trump might grease the skids for the growth of legal sports betting. Struggling DFS operators, however, are likely celebrating. New Jersey is moving closer to regulating that industry and those operators would like nothing more than to remain free from competition from legal sports books.

PASPA, makes it unlawful for:

(1) a government entity to sponsor, operate, advertise, promote, license, or authorize by law or compact, or

(2) a person to sponsor, operate, advertise, promote, pursuant to the law or compact of a government entity, a lottery, sweepstakes, or other betting, gambling, or wagering scheme based, directly or indirectly (through the use of geographical references or otherwise), on one or more competitive games in which amateur or professional athletes participate, or are intended to participate, or on one or more performances of such athletes in such games.

28 U.S.C. § 3702: PASPA does not require the use of interstate wire transmissions to be implicated. But read in connection with the Wire Act and UIGEA, it effectively outlaws all sports betting with extremely limited exceptions, most prominently the legal sportsbooks in Nevada.

Since 2011, New Jersey has been attempting to legalize sports gaming in its casinos. That same year New Jersey’s voters amended the state constitution’s exceptions for gambling at casinos and racetracks to allow the legislature to “authorize by law” sports gambling at those locations [N.J. Const. Art. IV, § 7, Para. 2(D) and (F).]. In 2012, the New Jersey Legislature enacted the 2012 Sports Wagering Act (2012 Act). The 2012 Act authorized licensed casinos and racetracks to conduct wagering on sporting events in accordance with the regulatory requirements applicable to their other gambling activities. Several sports leagues and the NCAA then challenged the 2012 Act under PASPA [See NCAA v. Governor of N.J., 730 F.3d 208, 217 (3d Cir. 2013) (Christie I), cert. denied, 134 S. Ct. 2866 (2014).]. New Jersey contended that PASPA is unconstitutional, arguing among other things that it violated the Tenth Amendment’s anti-commandeering principle, but the Third Circuit rejected that argument. Rather than continue to pursue that litigation, New Jersey passed a bill in 2014 that would have partially repealed its ban on sports betting. After the governor vetoed that bill, New Jersey passed yet another law (the “2014 Act”) that repealed New Jersey’s prohibition on gambling, “to the extent they apply” to sports gambling that meets five requirements: (1) the gambling is conducted “at a casino or gambling house” in Atlantic City or “a running or harness horse racetrack”; (2) it consists of wagering by persons “situated at such location”; (3) the persons placing wagers are “21 years of age or older”; (4) “the operator of the casino, gambling house, or running or harness horse racetrack consents to the wagering or operation”; and (5) the gambling does not include wagers on “a collegiate sport contest or athletic event that takes place in New Jersey or a sport contest or collegiate athletic event in which any New Jersey college team participates.”

Various sports leagues again challenged the 2014 Act, and the district and circuit courts again held that it violated PASPA. In again ruling that PASPA barred the 2014 Act, the Third Circuit noted that its holding that the “specific partial repeal which New Jersey chose to pursue in its 2014 Law is not valid under PASPA does not preclude the possibility that other options may pass muster.” In other words, the Third Circuit suggested to New Jersey that it could continue to try to craft a law that might pass muster or repeal its gaming laws altogether.

This time, rather than accept this ruling, New Jersey sought review from the Supreme Court. Obtaining review by the Supreme Court is notoriously difficult. It accepts only about 1% of all cases in which review is sought. Petitions filed by the government itself have the best chance of obtaining certiorari. The Supreme Court has suggested (in Supreme Court Rule 10) that various factors will influence its decision as to whether to review a case, including whether: (1) the decision below conflicts with the decision of a federal court of appeals or a state court of last resort on “an important federal question”; (2) the lower court decided “an important question of federal law” in a way that conflicts with a Supreme Court decision; (3) the court below “decided an important question of federal law that has not been, but should be, settled” by the Supreme Court; and (4) the lower court “has so far departed from the accepted and usual course of proceedings” as to require the Court’s “supervisory power”—a power rarely exercised. In a few cases, the Supreme Court asks that the federal government file a brief with its views, which it did in this case on January 17, 2017. Those cases are granted certiorari at a higher than normal rate, leading many commentators to believe that the Supreme court might indeed take up the case of New Jersey sports wagering.

But on May 24, the Solicitor General, through the acting Solicitor General Jeffrey Wall, filed a brief for the government arguing that PASPA was indeed Constitutional and that the case did not warrant review from the Supreme Court. In particular, the Solicitor General argued that PASPA’s “prohibitions are a permissible exercise of Congress’s authority to regulate state activities and to preempt state laws that conflict with federal policy in an area within Congress’s enumerated powers.” The Solicitor General did not identify which enumerated power gave it authority to regular gambling on a national basis, much less the authority to regulate it on an intrastate basis in New Jersey. Instead, the Solicitor General argued that the law did not violate the Tenth Amendment’s prohibition on commandeering because it did not affirmatively require New Jersey to do anything. New Jersey is free, the feds argue, to decriminalize sports betting altogether. It just can’t legally authorize it or regulate it. That freedom, therefore, is illusory. No one is suggesting a wholly unregulated sports betting market.

In contrast, New Jersey argued that PASPA’s purported preemption of state gambling laws presents an important question of federal law that should be decided by the Court. Because significant effort must be put into changing state laws, which then cannot be implemented without a change in the federal law, creating a circuit split or a large group of state petitioners is nearly impossible. If the Supreme Court adopts the Solicitor General’s view, PASPA is unlikely ever to be reviewed by the nation’s high court. Any reform will necessarily have to come from Congress – meaning additional years of delay and frustration for the backers of legal sports betting.

In the meantime, fantasy sports game operators will remain the only legal way (at least in many states) for players to engage in a game centered on real life sports contests. New Jersey took another step in this direction on Monday, when its Assembly passed legislation to regulate and tax daily fantasy sports. The Assembly voted 56-15 on a bill that would impose a quarterly fee of 10.5 percent of gross revenues on daily fantasy sports providers, slightly higher than the fee imposed in a Senate version of the bill. Assuming that bill becomes law after reconciliation with the Senate version and signature from Governor Christie, DFS will soon enjoy a prime position in New Jersey, while the sports gaming industry is left hoping that the Supreme Court catches its Hail Mary pass despite the Solicitor General’s opposition.